TO HER contemporaries, Charlotte Brontë came across as a “little, plain, provincial, sickly-looking old maid”. They were misguided; a retiring disposition and thick spectacles disguised the novelist’s passionate inner life. Brontë, born 200 years ago this month, endowed her heroines, particularly Jane Eyre and Lucy Snowe, with similar disguises—their simple gowns cloaking an ardour for love and sex. But while Brontë is known for writing impassioned, even angry, moral romances, what has passed by largely unnoticed is her facility to write erotica. That it was inspired by true occurrences makes the fiction all the more arresting.

In February 1842 Charlotte and Emily Brontë, seeking to improve their French and broaden their vistas, sailed for Belgium. The sisters were headed for the Pensionnat Héger, a boarding school located in a sunken, cobbled street in Brussels, run by Madame Zoe Héger and her husband Constantin. Emily was gone in less than a year. But for Charlotte, these gothic environs were life changing. She made prodigious strides as a writer and learned to temper her overwrought outpourings. It was also where her heart was broken.

The dark-haired, blue-eyed, cigar-smoking Constantin Héger was the cause. Seven years older than the 26-year-old Charlotte, he dressed in black and had a temper to match. But he was a gifted teacher who quickly recognised the extraordinary talent of his English pupils. Flinty Emily rejected his impress, but emollient Charlotte fell under his spell. As “his anger fiercely flamed,” she blossomed under his glower. Teacher and student began to exchange long pedagogic letters discussing Charlotte’s French exercises. Soon, Héger was leaving books in her desk.

For two idyllic months, this epistolary exchange continued until Héger’s wife put an end to it (the relationship was entirely platonic—though the Hégers must have had some idea of the powerful effect he was having on his student). On New Year’s Day in 1844, a devastated Charlotte returned to Yorkshire, from where she wrote piteous letters to her “black Swan” begging in vain for “a little—just a little” friendship.

Nine years later, in 1853, Brontë recreated the ecstasy and agony of those months in “Villette”—the fictional name she chose for Brussels. Her heroine, a plain-faced and seemingly colourless 23-year-old school teacher named Lucy Snowe finds herself falling in love with her choleric Belgian colleague. Unsurprisingly, Paul Emanuel is a dark-haired, blue-eyed cigar smoker. Lucy is drawn to his mind even if his chauvinism infuriates her: “Never was a better little man, in some points, than M. Paul: never, in others, a more waspish little despot.”

One evening, Lucy steals softly into a deserted classroom to discover Emanuel immersed in her desk. “His olive hand held my desk open, his nose was lost to view amongst my papers.” The reader is startled at the brazen snooping, but Lucy is unperturbed. She has known all along “that that hand of M. Emanuel’s was on the most intimate terms with my desk; that it raised and lowered the lid, ransacked and arranged the contents, almost as familiarly as my own”. Far from being a sneak, the nocturnal guest wants Lucy to know he has stopped by. Like Constantin Héger, he leaves behind little offerings: “Between a sallow dictionary and worn-out grammar would magically grow a fresh interesting new work, or a classic, mellow and sweet in its ripe age. Out of my work-basket would laughingly peep a romance…” All these offerings, Lucy explains with barely suppressed excitement to the entranced reader, have one peculiarity that settled the question of their provenance: “they smelt of cigars.”

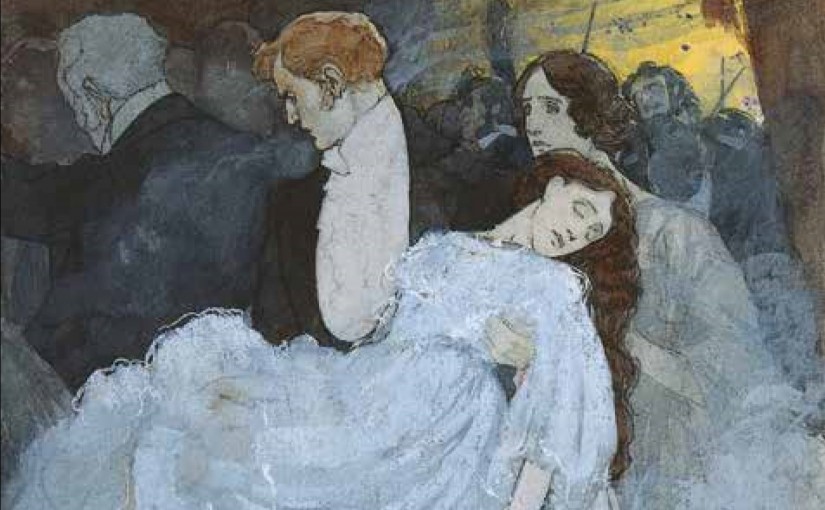

But though she is aware of his visits, this is the first time Lucy has actually caught her “freakish, friendly, cigar-loving phantom” in flagrante delicto. And she is exultant: “But now at last I had him: there he was—the very brownie himself; and there, curling from his lips, was the pale blue breath of his Indian darling: he was smoking into my desk.”

The carefully punctuated sentence cascades towards that final preposition: “into”. “At my desk” would have robbed the scene of its erotic charge and strikingly obvious symbolism. By bending forward and smoking into Lucy’s personal cache of her documents, books and needlework, it is as if Emanuel is exhaling into her very being. By touching her papers “with gentle and careful hand”, he is touching her. This fetishistic—yet strangely decorous—choreography of sublimation and suggestion unknots something inside her: “my morning’s anger quite melted: I did not dislike Professor Emanuel.”

Paul Emanuel is a likeness of Constantin Héger in every way, excepting one key difference: he is unmarried, and therefore free to be pursued. Everything is in place for Lucy and him to sail away in a blue haze of tobacco. But “Villette”—a tour de force of realism and fine craftsmanship—refuses any expectation of conventional happiness. It has a strange and ambiguous ending. Reader, she does not marry him.

Perhaps Brontë felt it would be dishonest to glibly surmount in fiction the despair and heartbreak she had experienced as a young woman in Brussels, when she fell headlong in love with an enigmatic Belgian professor. Despite a later marriage, she poignantly describes Héger as “the only master I have ever had”.